The wellbeing of older men and women throughout life in relation to living arrangements

Various experiences affect people’s health and wellbeing throughout their life course. he life course approach consists of four principles. (Elder 1998). First, people’s lives are a part of a certain historical period that affects them throughout their lives. Second, the impact of various life events on a person’s life course depends on the age at which the events are experienced. Third, as people’s lives are interdependent, social and historical influences are manifested through shared relationships. Fourth, people have agency – they shape their life course with choices and actions that depend on historical and social constraints and opportunities. Eesti puhul on oluline mõista, kuivõrd meie ühiskonna arengu ajalooline katkelisus on mõjutanud tänaste üle 65-aastaste heaolu taset ning kuivõrd nende prIn the case of Estonia, it is important to recognise how the social upheavals caused by the Soviet occupation and subsequent societal transformations have affected the level of well-being of people over 65 years old today and the extent to which their current choices help mitigate the effects of past negative events and enhance their sense of well-being.

Living arrangements are important in the context of relationships and wellbeing.

Research has shown that older men and women are affected by different patterns of wellbeing – while women seek security in living together, in the case of men, women’s greater social activity in older age helps to maintain the couple’s significant social relationshipsand thereby maintain men’s good health (Liu and Waite 2014; Abuladze and Sakkeus 2013). Middle-aged people often live with their parents for economic support (Grundy 2005), However, that means they are obligated to take care of their parents as the parents become more limited in their daily activities (Seltzer and Bianchi 2013).In both cases, being stressed about insufficient resources can reduce wellbeing significantly. But conversely, constant emotional support can increase wellbeing considerably. Parents and children have more frequent interactions and more commonly live together in countries with weak social welfare (Hank 2007). Due to recent demographic changes (e.g. the decreasing number of children), the wellbeing of the older population in such countries may deteriorate, as the corresponding national institutions and services have not (yet) developed enough to counterbalance the effects of demographic changes. (Reher 1998).

This article explores the gender differences in assessments of wellbeing in relation to forms of living arrangements and accumulated social and economic capital of people over the age of 65 (the birth cohorts born before the economic crisis of the 1930s, during the crisis of the 1930s and the Era of Silence (a period of authoritarian rule in Estonia) until the outbreak of World War II, and during the war and up until 1946.

In this article, we use the SHARE (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe) survey’s 2011–2013 data of Estonians over 65 years old (1,880 respondents, including 506 or 26.9% men). Regarding living arrangements forms formssence of children and/or parents in the household. Due to the small sample size, we grouped all the remaining types of living arrangements under ‘other’.We defined socioeconomic position by four childhood characteristics (number of books per person, number of rooms per person, parents’ highest level of education and economic situation in childhood household) nd four adulthood characteristics (respondent’s level of education, last occupation according to ISCO,1 income and value of net wealth adjusted to household size), mwhich were integrated into a composite index between 0 and 1 for childhood and adulthood respectively (Niedzwiedz et al. 2015), a higher value indicates a higher socioeconomic position.

1 ISCO – International Standard Classification of Occupations.

According to the life course approach, the capital accumulated in childhood and that accumulated later in life both play an important role in subsequent life events. These conditions shape the general standard of living, access to material resources, social prestige, and educational and cultural capital in old age. The circumstances of living arrangements, both in childhood and adulthood, can enhance wellbeing (if the accumulated capital is large) or reduce it.

We also used the health-related Global Activity Limitation Index (GALI2). We adjusted the analysis for the number of living children. people who have no (living) children cannot have children living with them or providing them support. After the Second World War, as Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union, many people of foreign (mostly Russian) origin settled here; they had lived outside Estonia during their childhood and often much of adulthood. In our analysis, we considered origin (born in Estonia or not) as a possible factor affecting the level of well-being.

We measured perceived wellbeing with the CASP-123 index (Hyde et al. 2003), which consists of 12 questions about feelings and situations on a four-point frequency scale. Scores can range between 12 and 48. Then we measured life satisfaction (Brown et al. 2004) on a scale of 0–10. For comparability, in both cases we converted the score to a scale of 0–100 (a higher score indicates higher perceived wellbeing or life satisfaction). In the case of older people, these two indicators measure different aspects of wellbeing and relate differently to living arrangements forms. The overall indicator of perceived wellbeing is more forward-looking, while life satisfaction is more of a retrospective appraisal of life. We will use the general term ‘wellbeing’ when discussing both perspectives together.

People’s wellbeing is firstly affected by what happens in the family.

In the last century, the development of Estonian family structures has seen a significant decrease in the number of children and an increase in the number of divorces, but it has also seen an increased frequency of forming new relationships. The long-standing gender gap in life expectancy has most impacted elderly women living alone. A general obligation to work and compulsory secondary education, which was introduced in Estonia in the mid-20th century, have increased individualism and women’s emancipation. For the same reasons, opportunities have expanded, especially for women, for managing on one’s own in old age. In this development, Estonia has kept pace with other developed countries. However, the social arrangements, which should support the needs of the elderly as their number increases, have not caught up with the changes. Therefore, we assume that, all things considered, the various patterns of familial living arrangements will continue to be essential for our wellbeing.

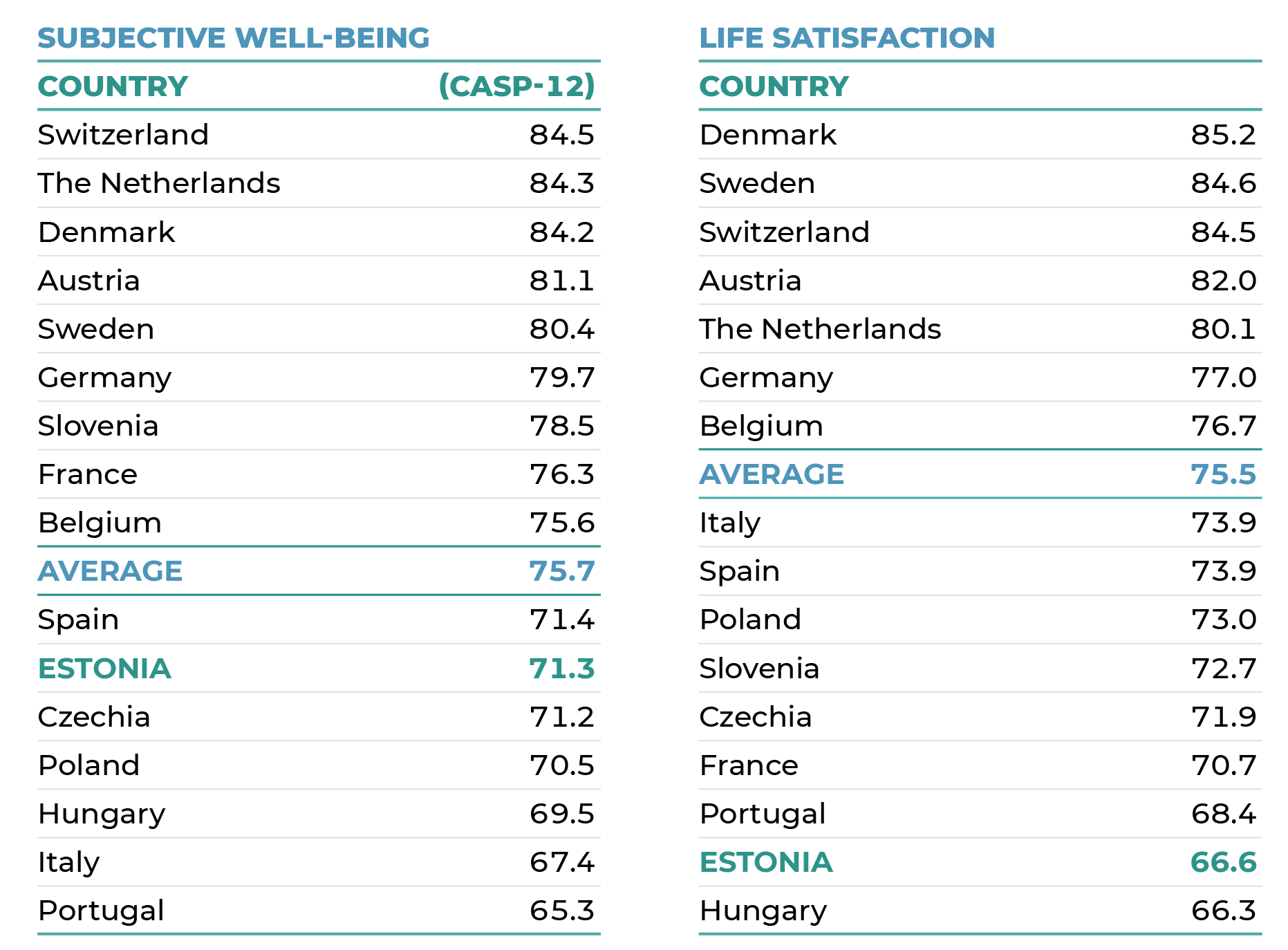

Estonian older people evaluated their perceived wellbeing at 71.3 points on average (Table 3.2.1). In terms of average scores, Estonia ranks in the last third among SHARE countries, together with the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Italy and Portugal. Estonians’ evaluation of their life satisfaction is on average 66.6 points. Among the SHARE countries, only Hungary has a lower score.When comparing both indicators with other countries, it is notable that the average assessments of wellbeing for older people are lower in Eastern and Southern Europe than in Western and Northern Europe.

2 GALI – Global Activity Limitation Index.

3 CASP – Control, Autonomy, Self-realisation and Pleasure.

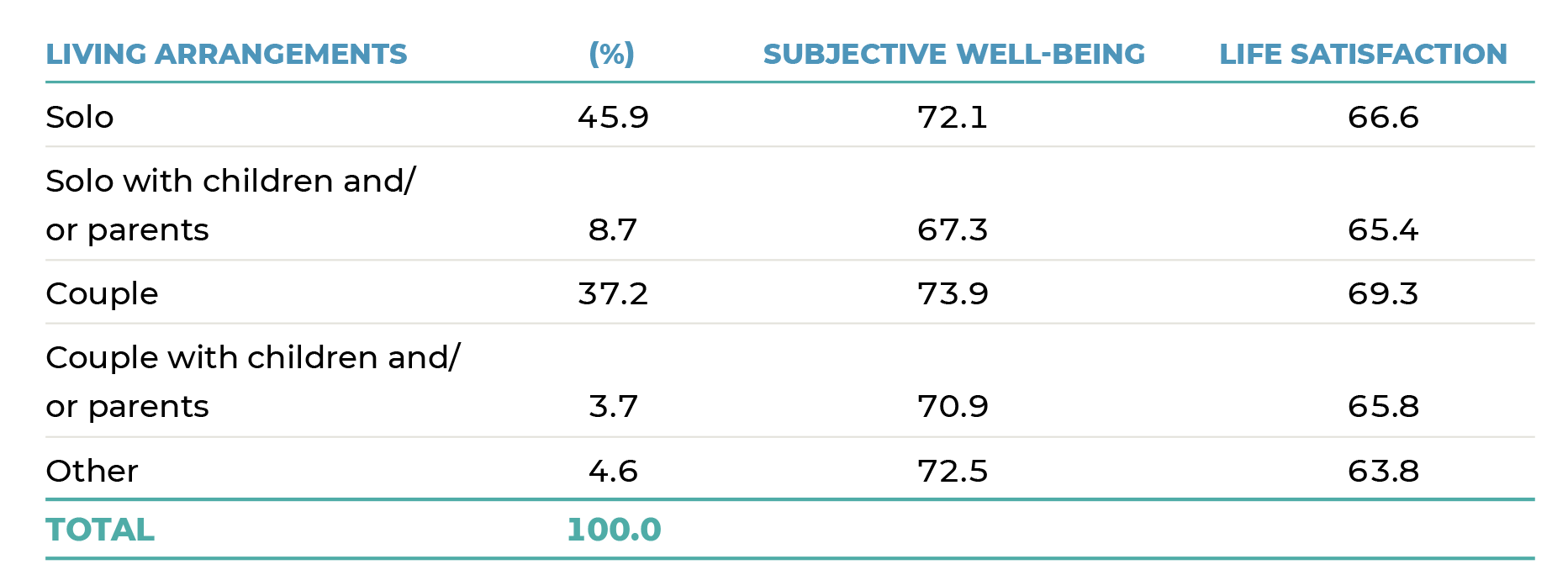

Two forms of living arrangements prevail among older people in Estonia: people living without a partner (singles) and people living with a partner. Singles are more likely than couples to live with others, such as their children or parents.

such as their children or parents table 3.2.2). In life satisfaction and wellbeing, couples living together have the highest average score, followed, in life satisfaction, by people living alone. In perceived wellbeing, the highest average is for people in ‘other’ forms of living arrangements, followed by people living alone.

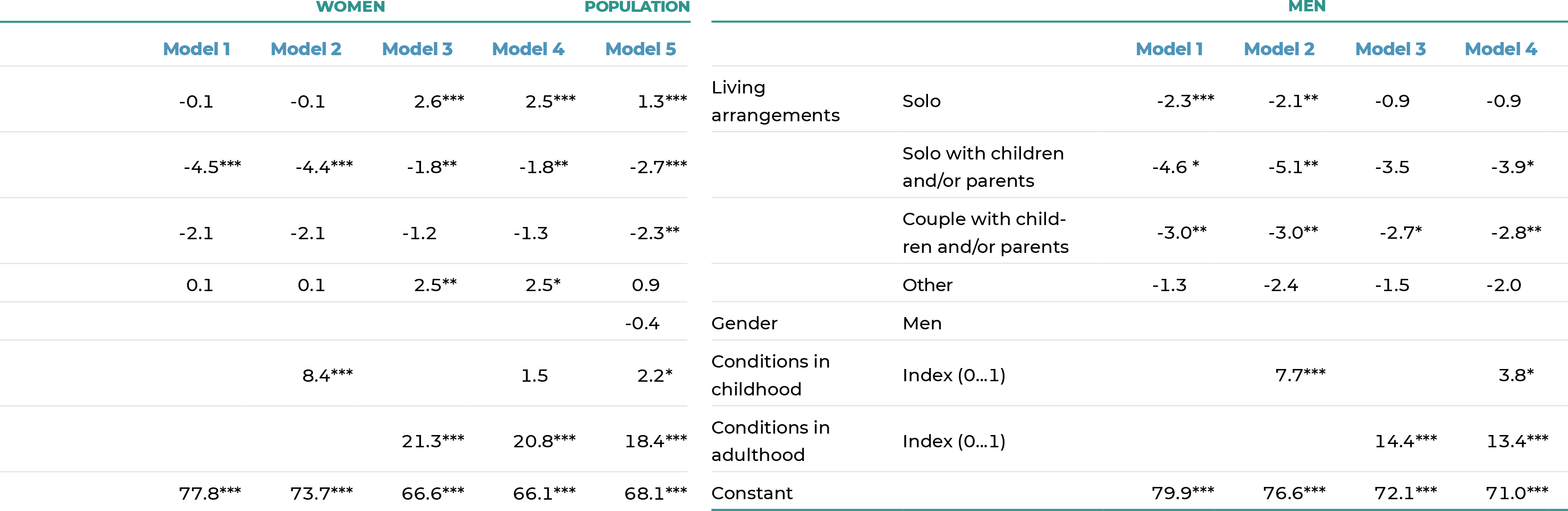

When analysing the correlation between forms of living arrangements and perceived wellbeing, certain differences between genders appear regardless of generation, health limitations, national origin or number of children (table 3.2.3). Men appear to thrive when living as a couple or in the living arrangement denominated as “other”, while all other forms of living arrangements significantly reduce their perceived well-being. This association also stands when considering the socioeconomic conditions in childhood. When adjusting for adulthood socioeconomic position, there is a significant change in the association between living arrangements and well-being: the negative impact of living alone or living alone with children and/or parents on men’s well-being becomes insignificant (when compared to living with a partner). In the final model for men, where both men’s childhood and adulthood conditions are considered, it appears that adulthood conditions have a bigger influence on the association between living arrangements and well-being. However, the combined effect of these conditions on the wellbeing of men who live with children and/or parents, whether alone or with a partner, is negative.

In the case of women, the associations are different. For women, living alone with children and/or parents is the only form of living arrangements that reduces women’s perceived well-being compared to living with a partner after adjusting for birth cohort, health-related activity limitations, birth origin and number of children. The associations of all the other forms of living arrangements and well-being do not statistically differ from the associations between well-being and living with a partner.

When considering the conditions in their childhood household, the relationships between forms of living arrangements and perceived wellbeing remain the same for women over 65. If we consider the socioeconomic position in adulthood only, then in the case of women, compared to living with a partner, living alone has a positive effect on wellbeing, and so does living with someone who is not a partner, parent or child (‘other’). Conditions experienced in adulthood increase wellbeing when living alone with children and/or parents. Similar associations remain between living arrangements and well-being after adjusting for childhood and adulthood socio-economic position simultaneously.

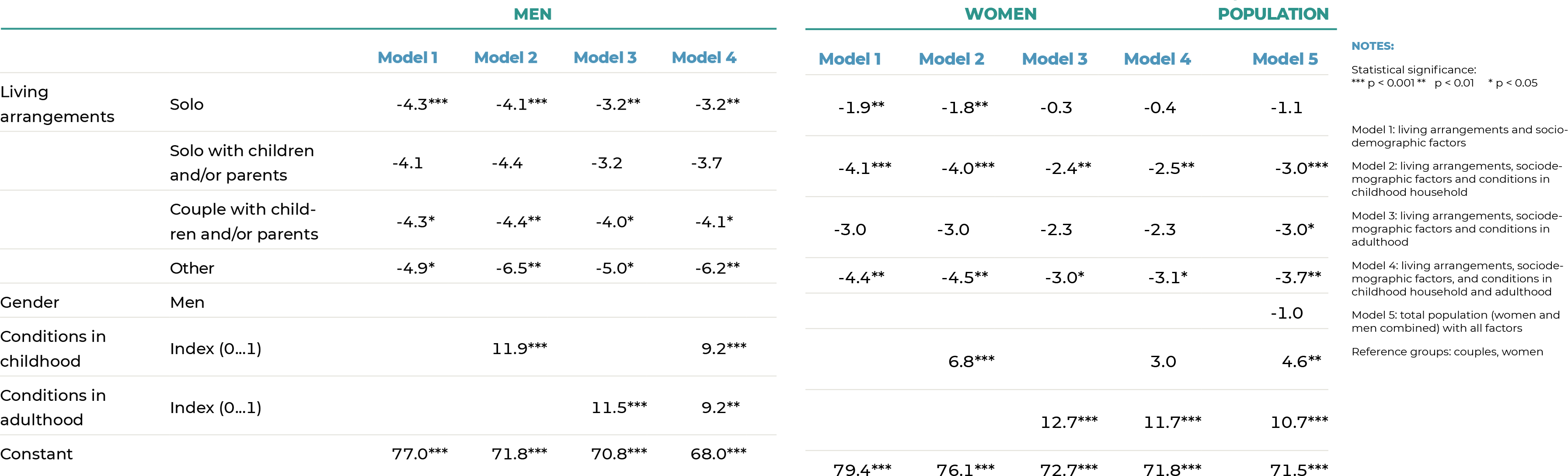

Similarly, life satisfaction, which is on average lower than the overall indicator of perceived wellbeing, reveals differences between men and women in relation to forms of living arrangements (table 3.2.4). Unlike perceived well-being, women have a higher average life satisfaction than men. For men, any living arrangements other than living with a partner reduces life satisfaction. Only the life satisfaction of singles living with children and/or parents does not differ from that of couples. When considering socioeconomic position in childhood, dissatisfaction increases among men who live in ‘other’ forms of living arrangements or with a partner and children and/or parents. Compared to living with a partner, men’s life satisfaction increases slightly in all other forms of living arrangements only after adjusting for socioeconomic position in adulthood. But their life satisfaction is still significantly higher when living with a partner.But their life satisfaction remains still significantly higher when living with a partner. When adjusting for socioeconomic position in adulthood as well as childhood, both turn out to have almost equal effect on the relationship between life satisfaction and living arrangements: men over 65 have a lower life satisfaction in all living arrangements other than living with a partner.

When we look at the relationship between women’s life satisfaction and living arrangements, after adjusting for birth cohort, health-related activity limitations, origin and number of children, there is no difference in satisfaction between women living with only a partner and women living with a partner and children and/or parents. All other living arrangements are less satisfying for women. A similar pattern persists when socioeconomic position in childhood is considered. If we adjust for socioeconomic position in adulthood, then neither women living with a partner and children and/or parent nor women living alone are any different in terms of life satisfaction when compared to women living with a partner. A better socioeconomic position in adulthood slightly increases women’s life satisfaction in all forms of living arrangements. If socioeconomic position in both childhood and adulthood is considered, the previously described pattern stands, because adulthood socioeconomic position, in particular, plays a significant role in the associations between women’s life satisfaction and living arrangements. Childhood conditions lose their significance in the relationships between women’s life satisfaction and living arrangements, while adulthood conditions increase their significance on these associations.

Summary

There has been a significant development in family formation since the 1960s, which has changed the roles of women and men in family, as well as in society. As we age, more life events accumulate that, in the context of societal development, have an impact on our wellbeing in older age. As a result of these changes, we see that the living arrangements best for the wellbeing of elderly women are opposite to those best for the wellbeing of elderly men.

People born in the early 20th century had relatively few children on average, and over the years, their children had a higher mortality rate than children of subsequent generations. Among the generations we analysed, in almost a third of the cases, staying alone was caused not by the partner passing away but by separation. After a couple relationship ends, men start a new life with a new partner more often than women do. The long-standing high mortality rate of men in Estonia has meant that many women have been left alone, especially in old age. Women deciding to stay single has a great deal to do with their level of education – which has been higher than men’s since the generation born in the 1930s – and paid employment, which ensures an independent income even in old age. As a result of this objective development, as well as expanded opportunities, more than half of women over 65 now live alone, while only a little over a quarter of men in that age group live alone. However, if they live with a partner, then, due to men’s lower average life expectancy and healthy life years, the man is usually the first to need support due to health problems. The primary helper, in this case, is the female partner living with him (Tammsaar et al. 2012).

Our analyses revealed that the associations with living arrangements and well-being of people over 65 are often for men and women in opposite directions. MMen’s perceived wellbeing is the highest when they live with a partner; it is the lowest when they are living with children and/or parents, either alone or with a partner. The perceived wellbeing of single women is similar to the wellbeing of couples when adjusting for the socioeconomic conditions in childhood and adulthood. Men living in any other forms of living arrangements have lower life satisfaction than when living with a partner. Women living alone have a higher perceived level of wellbeing and a more positive retrospective appraisal of life than women in any other forms of living arrangements (although the life satisfaction of women living with a partner is the same). At first glance, it seems paradoxical that older single women have higher well-being scores and the same level of life satisfaction as women living with a partner. However, there is a pragmatic explanation for this result in the Estonian context.

The positive effect that living alone has on well-being may be due to the greater burden placed on women to provide caregiving in other living arrangement forms. Even socioeconomic resources acquired in adulthood do not ease that burden. Several studies in Estonia have revealed that the informal burden of care is borne in particular by women over the age of 65(Tammsaar et al. 2012), that relieving the burden of informal caregivers improves their wellbeing (Bleijlevens et al. 2015) and that the need for that has significantly increased (policy guidelines ‘Hooliva riigi poole2017).

The positive effect that living with a partner has on men’s wellbeing suggests that their partner acts as a safety net, providing support in old age. Older women have larger social networks, and men living with a partner can be a part of that. As several previous studies have revealed, men living alone have the highest risk of health-related activity (Abuladze and Sakkeus 2013), and their significantly lower life satisfaction testifies to that.Among our research subjects – men and women over 65 – the difference in life expectancy has clearly visible effects on their forms of living arrangements. Thus, for men, the need for support arises earlier than for women, which is an additional reason why men value living with a partner (Hank 2007). Due to the usual age difference between men and women, when older women live with a partner, they often shoulder the responsibility of care when their partner’s health deteriorates.This can mean years of constant caregiving, in addition to stress from not having enough knowledge in the field of caregiving and emotional stress from the bad mood of the partner needing care. Living with parents, however, might often mean that the burden of care increases significantly for both genders, which is associated with decreasing well-being for both women and men. This may be more likely when they also have adult children living with them. The latter could increase the burden of caregiving and especially emotional or relational stress, which reduces wellbeing and satisfaction (Seltzer and Bianchi 2013). In Estonia, as in other Eastern European countries, caregiving is mainly left on the shoulders of a family. Thus the wellbeing of women can deteriorate significantly due to forced caregiving obligations, which in turn can generate future health problems for them.

The analysis highlights that the social and material capital accumulated throughout the course of life is important. Childhood socioeconomic capital (number of books per person, number of rooms per person, parents’ highest level of education and economic situation in childhood household) is connected to increased wellbeing for men living with a partner far more than it is for men living in any other living arrangements. However, better socioeconomic conditions in adulthood can compensate for this disadvantage, and the negative relationships between different living arrangements and wellbeing decrease among elderly men. Men’s greater dissatisfaction with life in living arrangements other than with a partner is explained by the fact that life satisfaction is assessed retrospectively: the conditions in childhood household and adulthood have equal influence. There is a significant positive relationship between the wellbeing of elderly women and living alone (there is also a slightly lower positive relationship among women who live with others) compared to living with a partner. This positive relationship is supported by the socioeconomic conditions in adulthood, in which case we assume that women, as the main caregivers and supporters of other family members in old age (Tammsaar et al. 2012) sare able to purchase the necessary services with better available resources and free themselves from related obligations. The long-term social pressure on women to be the main caregivers has led to a situation where women living alone in old age have the highest perceived level of well-being.

In conclusion the long-neglected need in Estonia to organise caregiving in a more egalitarian manner – and not allow the burden of care in old age to fall solely on women – has resulted in women’s well-being being best supported by different living arrangements than those that best support the well-being of men.

Abuladze, L., & Sakkeus, L. (2013). 27 Social networks and everyday activity limitations. Active ageing and solidarity between generations in Europe, 311−321. De Gruyter.

Bleijlevens, M. H., Stolt, M., Stephan, A., Zabalegui, A., Saks, K., Sutcliffe, C., … & Zwakhalen, S. M. (2015). RightTimePlaceCare Consortium: Changes in caregiver burden and health-related quality of life of informal caregivers of older people with dementia: evidence from the European RightTimePlaceCare prospective cohort study. J Adv Nurs, 71(6), 1378–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12561.

Brown, J., Bowling, A., & Flynn, T. (2004). Models of quality of life: A taxonomy, overview and systematic review of the literature. European Forum on Population Ageing Research.

Elder Jr, G. H. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child development, 69(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x.

Grundy, E. (2005). Reciprocity in relationships: Socio‐economic and health influences on intergenerational exchanges between third age parents and their adult children in Great Britain. The British journal of sociology, 56(2), 233–255. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tlu.ee/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00057.x.

Hank, K. (2007). Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(1), 157–173.

Hooliva riigi poole (2017). Hoolduskoormuse vähendamise rakkerühma lõpparuanne. Riigikantselei https://www.elvl.ee/documents/21189341/22261833/07_+Pkp+7+Hoolduskoormuse_rakkeruhma_lopparuanne.+Riigikantselei+2017.pdf/61c41a54-b73f-4d4a-ab5a-99926002ac4c.

Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., Higgs, P., & Blane, D. B. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging & mental health, 7(3), 186–194.

Liu, H., & Waite, L. (2014). Bad marriage, broken heart? Age and gender differences in the link between marital quality and cardiovascular risks among older adults. Journal of health and social behavior, 55(4), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146514556893.

Niedzwiedz, C. L., Pell, J. P., & Mitchell, R. (2015). The relationship between financial distress and life-course socioeconomic inequalities in well-being: cross-national analysis of European Welfare States. American journal of public health, 105(10), 2090–2098. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302722.

Reher, D. S. (1998). Family ties in Western Europe: persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review, 24, 203–234.

Seltzer, J. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2013). Demographic change and parent-child relationships in adulthood. Annual review of sociology, 39 (1), 275–290. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tlu.ee/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145602.

Tammsaar, K., Leppik, L., & Tulva, T. (2012). Omastehooldajate hoolduskoormus ja toimetulek. Sotsiaaltöö, 4, 41−44.